By David Westphal and Geneva Overholser

One of the dominant themes of political life these days is the ever-growing division between urban and rural Americans. Thomas Edsall described it this way in The New York Times: “A toxic combination of racial resentment and the sharp regional disparity in economic growth between urban and rural America is driving the upheaval in American partisanship.”

This topic sometimes makes its way to our dinner table discussions, where we try to understand what is driving rural and urban citizens so strongly apart. It hits home for us partly because of our journalism careers at The Des Moines Register, which for many decades was arguably the pre-eminent American newspaper covering farming and rural life. Iowa ranks second only to California in the value of its farm production, and even with population declines over the years, more than one-third of its residents are still classified as rural.

Chronicling this rich agricultural footprint was a huge part of The Register’s mission. The farm sector was both a major source of the newspaper’s advertising revenue (mainly classified ads) and a primary focus of news coverage. And it resulted in one of the rare daily newspapers that was delivered to homes in all of the state’s counties. It was, The Register boasted on its front pages, “The Newspaper That Iowa Depends Upon.” (At one point, the Sunday Register claimed a statewide circulation of more than 500,000 – a majority of the state’s households.)

Although vestiges of that time remain – the Register’s Annual Great Bicycle Ride Across Iowa (RAGBRAI) still draws thousands of riders each year – the newspaper’s statewide reach is long gone, a result of demographic, cultural and economic changes that have hit newspapers nearly everywhere. According to a recent NiemanLab report, The Register’s combined print and digital subscriptions have fallen precipitously, to below 40,000.

What did it mean when, for half a century, most Iowans were reading The Register? What was the impact of a newspaper that covered both rural and urban Iowans? It’s impossible to know with any certainty, of course. Consider this a thought experiment— one with some relevance to the divisions our nation is facing today.

In his book, “Covering Iowa,” William B. Friedricks wrote:

“Beginning in the 1870s, but really from the 1920s on, when its circulation began to take off, The Register sought to appeal to all Iowans. In so doing, it became a unifying force within the state. In an age when tensions between farmers and merchants, politicians and professionals, rural and city people, and even men and women were increasing, the paper provided a common meeting ground for all Iowans. It held the attention of the state’s various constituents by providing special sections to appeal to certain groups: it offered detailed coverage of agriculture; campaigned for programs of statewide interest, such as the promotion of good roads; and identified the views of Iowans on important issues in the Iowa Poll. Through such efforts, the Register brought citizens of the state together, and in many ways helped define what it meant to be an Iowan.”

It’s not the case, of course, that rural residents were all big fans of The Register. The newspaper routinely spotlighted problem areas in the farming sector such as damaging environmental practices or safety issues. It regularly chronicled the amount of federal subsidies farmers were receiving. The decidedly liberal orientation of The Register’s editorial pages was not a big hit in many rural homes.

But one thing we think is true: A great many farmers, agribusiness people, and small-town political and business leaders believed that, through The Des Moines Register, they were being seen – by the state’s political and business leaders and by ordinary Iowans across the state. Even as they in turn could see the lives of urban Iowans.

Throughout much of the 20th century, Iowa was the antithesis of the sharp rural/urban divide that now defines our politics. From Harold Hughes to Dick Clark to John Culver to Tom Harkin, Iowa fielded some of the most liberal politicians in Washington, often with robust support from rural voters. In 1984, Harkin’s first Senate victory, a majority of rural counties voted for him. And in that same election, about 40 percent of Iowa’s urban counties backed Republican Ronald Reagan over Democrat Walter Mondale for president.

There was a striking open-mindedness in the electorate, with voters gravitating to candidates and issues without the bindings of tribalism. That fluidity was still in evidence in Barack Obama’s two presidential victories, with nearly two dozen rural counties supporting his 2012 successful re-election bid. Not so today, of course. In the last two presidential elections, all of Iowa’s rural counties have voted for Donald Trump.

In an editorial after the 2020 election, The Register lamented the state’s new pattern of “us vs. them” voting, which it said is permeating politics at all levels. “The risk for Iowa,” the editorial said, “is that it feels as if the state’s historical rural-urban divide is now on steroids, pushed to a new extreme…”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, we find ourselves believing that The Register’s decline, and its retreat from a statewide footprint, is a significant part of this story. Again, impossible to prove. But perhaps examining what has been lost, or nearly lost, from the paper’s report could shed some light.

At one time, The Register had full-time correspondents in eight Iowa cities beyond Des Moines. It had stringers in all 99 counties. It had a fleet of cars that reporters and photographers would use to drive across the state to cover athletic contests, cultural events and spot news developments. The Register was wonderfully innovative. In the 1920s it was one of the early newspapers to purchase airplanes for covering spot developments around the state. At one point, according to George Mills’ book, “Things Don’t Just Happen,” the editors employed carrier pigeons to fly film of an execution at the state prison in Fort Madison to Des Moines. (The pigeons never arrived.)

Three examples of The Register’s statewide orientation:

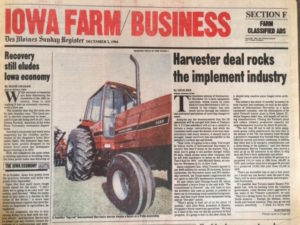

- Farm and agribusiness coverage. For much of The Register’s life, it had a daily page or more of farm news. The Sunday Farm/Agribusiness section, though, was the showcase, filled with rural-Iowa stories and, not coincidentally, pages of classified ads for farm equipment, livestock, auctions, and so on. The farm/business staff was stocked with some of the best journalists in the room. But that room was only part of the story. The Register’s Washington Bureau arguably had the strongest farm coverage of any DC staff – from reporters like Nick Kotz, Jim Risser, George Anthan. One of the byproducts of their coverage was to make Iowa more internationalist, showing how the state’s multibillion dollar farm exports tied the state to a global economy.

- Political coverage. For nearly 50 years, The Register’s political coverage has been recognized mainly for its chronicling of the Iowa Caucuses and the bellwether Iowa Poll. But day in and day out, reporters like Jim Flansburg and David Yepsen would reflect the local and regional politics of the state, traveling to county conventions, steak fries and other political events across Iowa. Former Gov. Robert Ray once remarked that he had a significant advantage over other governors. Because of The Register, he said, he knew what Iowans across the state knew.

- Sports coverage. For many years, and even today, The Register’s sports coverage has been anchored in its dispatches on the University of Iowa and Iowa State University. Almost as important, though, was its commitment to statewide high school sports. The Register sought to print the scores of every football and basketball game from the state’s 400-plus high schools, and would produce weekly columns and features on high school athletes. Every Friday night in football season, a reporter and photographer would travel to a “Spotlight Game,” often played in one of Iowa’s small towns. They would produce a short story and single photo that sent quite a message: What happens here on a Friday night, miles away from Des Moines, matters to us.

Coverage like this was possible, of course, only because the newspaper’s statewide orientation worked as a business model. It doesn’t anymore. The Register, once with a full-time news staff of 225, now has fewer than 50 reporters and editors. It still tries to cover farming and rural Iowa, but with a reach and strength reduced by orders of magnitude. This is true not just of The Register. Coverage of rural matters has vastly declined in recent decades, even in newspapers like the New York Times and Washington Post that could well afford it.

Nearly 25 years ago, Robert Putnam published “Bowling Alone,” in which he argued that “social capital” was in sharp decline in the United States, a result of dwindling participation in civic life – not just in bowling leagues but in community organizations, in churchgoing, in voting participation and yes, in newspaper readership. A Cornell University professor, Suzanne Mettler, said that because of these “cross cutting relationships … people had a sense that we’re all in this together; we’re all citizens of this country with a common project, even if we differ on policy issues.”

There may be many contributors to our current us-vs.-them climate. The internet. Social media. Extremist cable channels. Talk radio. Growing income disparities. A nation that becomes ever-less rural. But, as Putnam argued, a primary cause may also be the weakening of institutions like the newspaper that brought people of different backgrounds into contact with one another.

Last weekend on NPR, Atlantic writer McKay Coppins, who has studied the impact of newspaper closures and downsizing, said this: “There’s a pretty big body of research that shows that when a local newspaper vanishes or is dramatically gutted, it tends to correspond with lower voter turnout, increased polarization, a general erosion of civic engagement. It makes it easier for misinformation to spread, for conspiracy theories to spread.”

And that makes it a nationwide problem because newspapers are in fast decline virtually everywhere, with scant prospects for a turnaround.

So what is the case for optimism here, particularly in addressing the urban/rural divide?

- Ultimately, the hope is that digital news can help provide solutions. One early attempt: the year-old Rural News Network, which includes about five dozen news sites and organizations that focus wholly or partly on rural issues. Organized by the Institute for Nonprofit News, the network is anchored by the Daily Yonder in Kentucky and Investigate Midwest in Illinois (including its Iowa Watch newsroom), and seeks reporting partnerships among its participants. This is an initiative that merits the support of charitable foundations and wealthy benefactors, and should grab the attention of national newspapers and TV networks for partnership possibilities. Then there is the growing list of local and regional digital sites, such as Julie Gammack’s Iowa Writers Collaborative, which offer increasingly rich reporting on their diverse populations.

- The New York Times, the Washington Post and TV newsrooms – those still with working business models – should return to the time when they gave much broader coverage to farming and rural issues. They are certainly on the case covering the pitched, ideological political battles taking place in rural states, and rightly so. But there is so much more to farm and small-town life, and the big news organizations would do themselves, and the country, a favor by better reflecting it.

Rural and urban Americans seem increasingly to find themselves utterly foreign to one another. In looking back at The Register’s (and perhaps some of Iowa’s) best years, we are reminded that this is not an unsolvable problem.